"Today I'm comparatively extroverted, and at times I certainly can cuss along with the best of them - and surprise the entire family when I do. As a matter of fact, Carol's actually 100 times more prim and proper than I am. The real trashy item when it comes to the two of us being together. But that's in private."

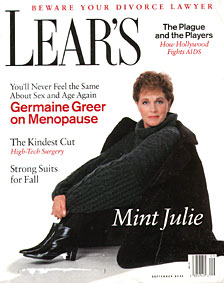

Lear's Crisp. Pert. Cheery. Bawdy. Sexy. Tough. Dressed in a plain, fitted black gown, Julie Andrews stands on the shallow platform of the Presbyterian Church in the old whaling Seated in front of her in this pristine church are local townspeople intermingled with old New York stage friends from her early days on Broadway - when My Fair Lady turned this slender English girl with ramrod posture and a radiant voice into a budding American icon. Her determination jaw and upturned, freckled nose were trademarks on her luminous, slightly impish face: She was the gingery girl you could bring home to Christmas dinner to charm your grumpy grandpa, the funny, tender, no-nonsense sis or mom who won our affection. According to Alan Jay Lerner, who wrote the lyrics for My Fair Lady Julie Andrews achieved her mega-stardom with nothing to offer but talents industry and an uncorrupted heart". This concert in Sag Harbor - the climax of six weeks of rehearsal is Julie's gift to her 29-year-old daughter Emma Hamilton, whose father is Julie's first husband, the brilliant stage designer Tony Walton. The proceeds will go toward the construction of a new town theater to be headed by Emma and Sybil Christopher, Richard Burton's first wife. During the concert, Emma sits in a front pew beside her new husband, Stephens her face aglow. It is an intimate evening the first time Julie Andrews has ever sung in public without an orchestra. She is 56 now, and in the 30-odd years since My Fair Lady her voice has matured-it is darker, more expressive, with a touch of torch. She sings songs by the likes of Jerome Kelvin Harold Arlen, Kurt Weill - personal choices that form a small self- portrait of the optimistic Julie who still believes in spring and romance, who relishes lyrics like, "Oh, how I love this crazy world'' . . . "Stay old-fashioned with me'' . . . "Oh boy I'm lucky''! But there's another Julie Andrews, a tough, even salty broad who wants to be heard. Sitting on a stool, she tells a rollicking story about Rex Harrison breaking wind on stage during My Fair Lady. And with mock irritation, she sings a song written by two close friends - a satire on her saccharine image that allows her to refute some of its unappealing aspects. "Hold on a minute," she sings at one point. "I'm not cold. Aloof, perhaps, or shy, perhaps, or keeping under wraps, perhaps. But cold?" A week later Julie Andrews is talking in her large Los Angeles office, where everything is white-couch, carpeting, walls, desk, and grand piano - save for three palm trees, an effulgence of flowers, and a tiny, red-framed four-leaf clover. She lives nearby, with her second husband, the movie director Blake Edwards, and their two adopted Vietnamese daughters Amy; 18, and Joanna, 17 (Julie also helped to raise Blake's two children, now grown, from his first marriage). But home life is kept at a distance from business: Directors, costumers, board members from her charities, even her arranger all come as an interview to see her at the office. As an interview subject, Julie Andrews is the very model of Mary Poppins natural, helpful, eager to do a good job, rigorously truthful - even stimulated by questions that force her to be specific about easy generalities. Intermittently, though, there are glimpses of a more private, reserved woman, who hides her deepest thoughts behind her warmth, hides her imagined defects and anything else that might cause another person pain. People are so keen to bracket you. Those movies are forever young, so the image does keep coming back on one. And obviously the prim and proper must come across, because people do harp on it rather a lot. I've also been called "the nun with the switchblade," so there must be that too, a reticence, politeness, perhaps a manner, I don't sort of splash my affections around. I suppose a part of me stood to one side and watched. I envy my chum Carol Burnett, her ability to be instantly warm with people. I think she probably is reserved, like me. I think we are both shy. Occasionally I look at myself as a young performer on a television show or something, and I think, Jesus God, there's nothing there. Slightly out to lunch, as they say. Today I'm comparatively extroverted, and at times I certainly can cuss along with the best of them - and surprise the entire family when I do. As a matter of fact, Carol's actually 100 times more prim and proper than I am. The real trashy item when it comes to the two of us being together. But that's in private. In public my greatest fear is making an idiot of myself. I mean, My God, any second now my knickers are going to fall. Julie Andrews as born on October 1, 1935, in Walton-on-Thames, a London Suburb. Her father, Edward Wells, was schoolteacher; her mother, Barbara, was a pianist and a colorful extrovert who loved entertaining audiences and friends. The couple divorced when Julie was four, and she stayed with her mother, while her younger brother went with her father - partly because neither parent could afford to have both children. Barbara's second husband was Ted Andrews, a boisterous, natural-born salesman who was an alcoholic. He was blessed with a rich tenor voice, and he and his wife became a vaudeville act, touring England. One day, Ted Andrews discovered that his stepdaughter has a freak voice, routinely capable of hitting F above top C. Julie remembered that "once, to the amazement of me and all the dogs in the area, I actually hit a C above top C." Andrews sent her to a singing teacher and put her through daily two-and-a-half-hour practices. At 12 Julie joined the vaudeville act, and in her first major appearance, at London's Hippodrome, in a revue called The Starlight Roof, she stopped the show with a bastardized version of the aria "Polonaise," from Mignon.

Those were bleak years, when I was on the road in my teens. The theatres were ratty. And I couldn't really afford to stay in a hotel, so I stayed in digs. My mum must have worried dreadfully, because she would say to people, "You're going to be on the same bill, could you keep eye on Julie?" Every week I played a different town; some had very tough audiences. I was this idiot in her little dress with bows and Mary Jane's, trying to do operatic arias to the second house Saturday night, when everybody had had more then a few drinks. But nobody booed me off the state. I've always maintained, excuse the awful analogy, that big dogs don't harm little puppies. They know I was an innocent, and I also had these awful show biz smarts about how to whiz them and wow them - so I squeaked by. Home was my rock, a little wobbly but the only one I knew. I wanted to be sure the family was all right, so I used to travel from Scotland overnight on a Saturday just to be home in Walton-on-Thames for Sunday. Then I'd go back to Manchester on Monday - anything to break the amount of time I'd be away. Whenever I came back from touring and headed down our garden path, I felt safe and secure. My brothers were there and my own bedroom. It was like, "Good, I'm home!" - even though my parents would sometimes have hot and heavy rows. I thought at any moment things could explode, and I was worried that my mother would get hurt. There were periods when my father was a teetotaler, but when he'd been drinking, he was dangerous. He tried to be kind to me, which must have been difficult, because I had a hard time liking him. I mean, here came this powerful, stocky built man taking Mummy away - and all that kind of thing. As you go through life - especially as you have your own children - you learn pretty quickly that there are no real heavies. That may sound like Pollyanna . . . but you become very tolerant after a while and, hopefully, compassionate. My mum and my stepfather had such terrible upbringings. He was an abused kid and so was she, and you see enormous patterns going back generations. Eventually, I felt extremely responsible, felt that I had to take care of the whole family, that it was only me being an adult around the place. So I was always a good little girl, trying to preserve what was good, being cheerful, and saying, "Things aren't so bad. We'll manage." And, of course, we did. Given my situation, I was lucky to have an identity something that gave me some accolades and attention. I think I would have been the most lost soul in the world if I had not been able to sing. So I got a certain kind of awe from people. Then, at 17, my voice went through enormous changes of gears, and I couldn't reach those high, high notes that were my stock-in-trade. It was very frightening. At the same time, my education wasn't the kind that gives you an enormous amount of confidence; Really, my formal schooling was very limited. To this day I still feel that I either have to shut up or prove that I'm not a dummy. I get tongue-tied. Jesus, I hope I'm not whining about my background. I hate people who carry on. I have a lot of the British stiff upper lip. When Julie was 18, she was invited for a year in a New York production of The Boy Friend. She was terrified of leaving England and home for so long, fearful of what might happen to her family without her care taking. In agony of indecision, she visited her real father, whom she adored. Edward Wells was encouraging, and Julie mustered the strength to go. The decision, of course, was momentous: Right after The Boy Friend, she was cast in the Broadway production of My Fair Lady. |

town of Sag Harbor, Long Island, where the sailors and captains of the 1840s came to pray for a safe and profitable voyage. Behind her at a grand piano, sits her conductor- arranger of 20 years, Ian Fraser framed by two Corinthian colleens.

town of Sag Harbor, Long Island, where the sailors and captains of the 1840s came to pray for a safe and profitable voyage. Behind her at a grand piano, sits her conductor- arranger of 20 years, Ian Fraser framed by two Corinthian colleens. Within a year she was singing in a command performance for the king and queen; soon she had top billing in the act and was the family's primary breadwinner. But as vaudeville in England died, so did the public's interest in Ted and Barbara. When Julie was 15, Ted retired and Barbara stayed home to care for him and their two sons. Julie was still in demand, though, and she continued on the road, traveling first with a governess and then on her own.

Within a year she was singing in a command performance for the king and queen; soon she had top billing in the act and was the family's primary breadwinner. But as vaudeville in England died, so did the public's interest in Ted and Barbara. When Julie was 15, Ted retired and Barbara stayed home to care for him and their two sons. Julie was still in demand, though, and she continued on the road, traveling first with a governess and then on her own.